Are Plato and Aristotle fundamentally different?

- Oliver Harflett

- Aug 5, 2025

- 8 min read

How do Aristotle’s ideas differ from Plato’s? And are these differences fundamental?

In The Republic, Plato writes how Socrates argued with others over what justice is. The different people Socrates interacts with in The Republic represent different schools of thought in Greece. For example, Cephalus, who represented ‘traditional’ notions of justice in Greece simply asks Socrates in frustration: “…concerning justice, what is it?” (Book I, The Republic.)

After a lengthy, famous Socratic dialogue (elenchos) with a huge array of different characters representing different ideas over several books, Plato slowly begins to settle on what justice is. He begins by articulating what justice is in an individual person. He contends that justice is a balance between three different parts of a person’s being (psyche.) These are reason, appetite and spirit (Book IV, The Republic.) The ‘just’ person is someone who embodies these three traits in harmony and balance with one another. Too much or too little of any one of these will start to cause problems - not just for the individual but for others too. If a person has these three facets in balance with one another, then virtue is more likely to arise. In other words, Plato believes justice emerges from the well-ordered individual (Book IV, The Republic.)

In Plato’s thought, justice in a society mirrors justice in the individual person. A just society is a balance of three different roles that people should perform. We might dub these ‘social classes’ today, but social roles is a more accurate term to describe Plato’s thinking. These are roles a person must fulfil, not just classes a person is born into. These three roles are Guardians, Auxiliaries and Producers. Explained briefly:

Guardians reflect the reason-part of the psyche. Guardians act as rulers of the Republic. They are educated and trained for this role from being 8 years old until they are at a minimum 55 years old (Book VI, The Republic.)

Auxiliaries reflect the spirit-part of the psyche. Auxiliaries act as the protectors of the Republic. They fulfil the roles of the military, police force and civil servants in today’s terminology.

Producers reflect the appetite-part of the psyche. Producers act as commoners of the Republic rather than politicians or rulers. They fulfil their duties through their vocations (Book IV, The Republic.) The Producers are to be masters of their respective trades, not jack-of-all-trades. They are the breadbasket and backbone of the Republic. They are the farmers, craftsmen, workers, etc.

So, when the Republic is balanced between all these different roles, justice is at its most likely to flourish. It mirrors his idea that justice is more likely to flourish within the well-balanced psyche.

With this in mind, Aristotle conceptualises justice in a more empirical and analytical way than Plato’s more introspective and idealistic approach. Like Plato, Aristotle is interested in defining justice. He is critical of others' ideas of justice. He writes that,

“…all men cling to justice of some kind, but their conceptions are imperfect, and they do not express the whole idea.” (Book III, Part IX, Politics.)

He believes one facet of justice is to follow the law when it is fair (Nichomachean Ethics, Book V.) After all, if people did not heed any laws, the result would be moral chaos. And moral chaos is a sure recipe for injustice to flourish. However, obeying the law full stop is not a sufficient definition of justice for Aristotle, because some laws are unfair and unjust (Nichomachean Ethics, Book V.) If one obeyed these laws blindly, they would be behaving unjustly, thereby undermining justice, a very important virtue to Aristotle.

Aristotle argues there are two types of justice in society: distributive justice and restorative justice. An example of distributive justice would be a good carpenter would be paid more for his work than a lousy carpenter should. In Aristotle’s words:

“…they who contribute most to such a society have a greater share in it than those who have the same or a greater freedom or nobility of birth but are inferior to them in political virtue.” (Politics, Book III.)

One might call this a meritocratic approach to justice. Whoever does the best job should get the best rewards. In contrast, an example of restorative justice would be this: a thief steals £100 from someone. To ‘restore’ justice, the thief could be fined £100, or work to earn £100 for the victim, or be forced to give back the £100 he stole. Aristotle's conception of restorative justice is akin to the Biblical ideal of, "an eye for eye, a tooth for a tooth..." (Exodus: 21:23 - 27) The just society should punish the guilty in exact proportion to the harm they inflict.

Another definition Aristotle provides is this - justice is a ‘golden mean’ between two different types of injustice: having more than one deserves and having less than one deserves. (Nicomachean Ethics, Book II, Part I.)

Like Plato’s theory, justice is very much about balance, albeit in a much less metaphysical or psychological way. Aristotle’s idea seems to be almost mathematical. It is closely tied into his other idea of the goal (telos) of being a person. This goal is fulfilment (eudaimonia.) In order to work towards eudaimonia, a person must cultivate their own virtue by performing virtuous acts. One of these chief virtues according to Aristotle is justice (Nichomachean Ethics, Book V, Part I.) Aristotle mirrors Plato here – that a just society is more likely to occur when its citizens behave justly. The person who pursues the goal of living a fulfilling life is more likely to pursue justice. By ordering the self, you order the society.

However, something Aristotle objects to in Plato’s Republic are ideas on the family. Plato believes the traditional nuclear family (a mother and father raising their child) should not be allowed for the Guardians of the Republic. Instead, Guardians should have arranged marriages planned by other Guardians, and these marriages should be terminal, meaning that they are annulled once the wife gives birth. These arranged, terminal marriages occur at special festivals with sacrifices and songs (459E, Book V, The Republic.) This means that the newly wed couples will conceive at a similar time and that the wives will give birth at a similar time. It is worth noting that there are a strict set of regulations on which Guardians are allowed to marry, ensuring only the fittest and strongest Guardians produce Guardian children (459 – 461, Book V, The Republic.) When a Guardian is born, it is to be confiscated and raised as a member of the Guardian community. It means the Guardians should not know who their children are, nor the children know who their parents are. Plato argues that this is necessary to preserve the raison d’être of the Guardian class: to guard the state. The Guardians' parent becomes the Republic in a sense.

Aristotle objects to this. He argues that the family is important for all citizens of the Kallipolis (beautiful city) including the ruling class (aristi politeia.) There are several reasons for this:

Firstly, the family is a fundamental unit of the Kallipolis because family life often teaches people an important virtue: responsibility (Book I, Politics.) By learning how to be a responsible person, the enlightened citizen will make a better ruler, since they have already practiced responsibility: towards a parent, a child, a relative, etc. To abolish the family would only interfere with this process.

Secondly, he argues Plato’s idea of rulers sharing their wives and children will mean that rulers will care less for them than within a family structure (Book II, Politics.) The vital virtues of respect and love are much more likely to be learned in a natural family environment than in a Platonic academy. These virtues would be ideal in an enlightened ruler who emerges from Aristotle's Kallipolis, and said virtues would be less likely to emerge in Plato’s Republic.

Thirdly, Aristotle states that just as the ‘nuclear’ family emerges naturally, so too the state (polis) emerges naturally (Book I, Part VI, Politics.) The state is not something which can be reconstructed as one desires, because it something that has slowly emerged over a very long period of time and has been shaped by a plethora of people over hundreds of years. Because Aristotle believes in the longevity and historicity of the state, he rejects Plato's notion of 'starting anew' from scratch in his Republic.

Aristotle seems to be more pragmatic in his views on the family and the ruling class, whereas Plato seems to be more idealistic. Aristotle subtly criticises Plato’s approach in Politics. He states:

“Mastership and statesmanship are not identical, nor are all forms of power the same, as some thinkers suppose.” (Book I, Part VI, Politics.)

In other words, just because a man is the master of his own psyche, it does not mean that he will make a good statesman.

So, does Aristotle fundamentally differ from Plato?

On the one hand, I believe the two philosopher’s approaches to justice are quite different. Plato’s notion of justice is quite psychological , whereas Aristotle’s is a more sociological perspective. However, I do not think this is a fundamental difference. They both touch upon the importance of a well-grounded, well-balanced psychology of the individual as being the foundation stone of a well-balanced, just society. Though the two walked down different paths, their destination is almost the same place - a society based upon the balanced scales of justice.

On the other hand, their views on the structure of a society seem to be irreconcilable to me. Aristotle thinks the state emerges from the family, whereas Plato thinks the Guardians should emerge from the Academy, without a family. Furthermore, Plato seems to think the family unit is a dangerous distraction for rulers, whereas Aristotle believes it is vital unit for making rulers. These are what I would call fundamental differences.

So what is my conclusion? Whilst both Plato and Aristotle lived in a similar environment, historical context, held similar values and shared goals, their differences are irreconcilable. They want the same outcome, but go down completely different routes to get there, and these differences are too great to coexist in the same ideal society.

The ideal state of Aristotle is not the ideal state of Plato. To cite but a few examples:

Plato's ideal ruler is the famous Philosopher-King. Aristotle's is the educated middle classes.

Plato's Republic is an 'enlightened' monarchy based on social strata where each person fulfils their assigned role. Aristotle's Republic is an oligarchy of participating middle class voters in a 'semi-democracy.'

Plato is anti-democratic, whereas Aristotle is more democratic.

Plato is a political revolutionary by nature, whereas Aristotle is a political evolutionary.

Plato's state is based upon abstract ideals, whereas Aristotle's is based upon human nature and the nuclear family.

Put another way, Plato is idealistic, whereas Aristotle is pragmatic.

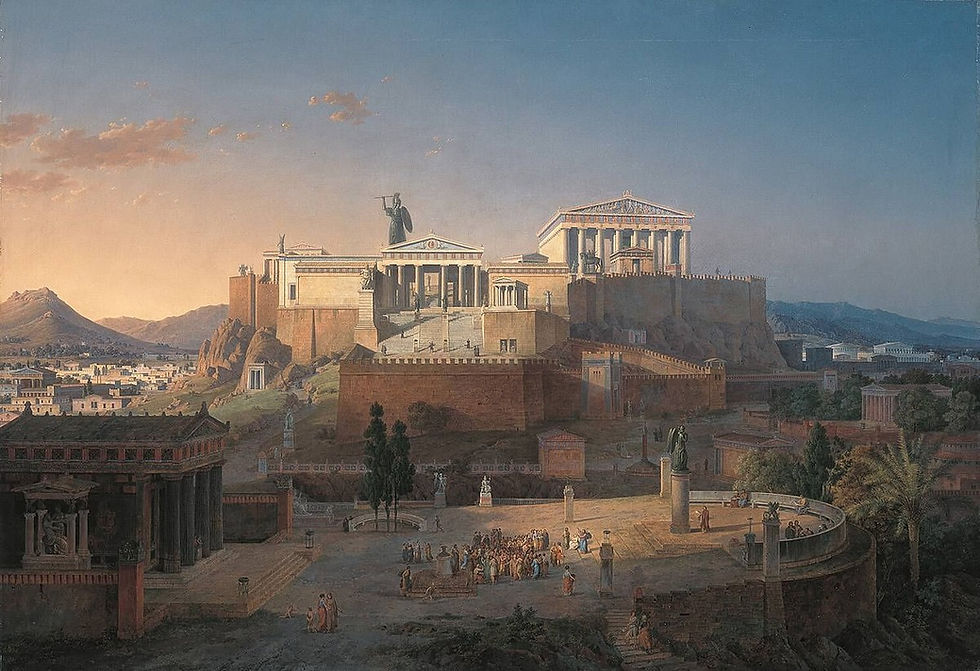

![Philosophy enthroned upon the globe, in reference to Kant's allegory in his book 'Critique of Pure Reason.' Plato famously stated that, "There will be no end [...] until philosophers become kings or until those we now call kings really and truly become philosophers.” (The Republic.)](https://static.wixstatic.com/media/3e31d7_84442e1561a8424180fe9d9f313ffa87~mv2.png/v1/fill/w_850,h_1110,al_c,q_90,enc_avif,quality_auto/3e31d7_84442e1561a8424180fe9d9f313ffa87~mv2.png)

For these reasons and many others, I believe the two's views on politics are fundamentally different. But each man's contribution to political philosophy has been immense. The examples are endless, but to name a few:

The word democracy is based on demos, the Greek word for people.

The medieval system of feudalism reflects the ideals of Plato's Republic. Three estates based upon three roles that intermingle with one another; the clergy, the nobility and the commoners. Each class upheld the other two, just like in the Republic.

Aristotle was studied so much in medieval Europe, he was simply called 'The Philosopher.'

Plato's Republic and Aristotle's writings inspired the founding fathers of America shape their new country after breaking away from Britain - the United States of America, a long-standing republic.

Plato's Republic even influenced Sigmund Freud's theory of psychoanalysis. Freud's division of the mind into 3 components (id, ego, superego) was directly influenced by Plato's division of the psyche into 3 parts (appetite, reason, spirit.)

It seems good philosophy is not often about agreement. It is often based upon respectful disagreement. To see how strong the others' idea is. To see if it stands up to scrutiny. Or as Nietzsche put it, philosophising with a hammer. The dialectic between Plato and Aristotle (mentor and student) has born some very productive fruits for over 2000 years. From the foundations of democracy in ancient Athens, to the Middle Ages across Christendom and up to the present day, the political legacy of both Plato and Aristotle is immense.

Bibliography

Aristotle (c.340BC) Nichomachean Ethics

Aristotle (c.350BC) Politics

Exodus 21: 23–27, Holy Bible. New International Version

Plato (c.360BC) The Republic